Homo Sapiens Sapiens: Evolution, Origins, and Characteristics

Homo Sapiens Sapiens

Also known as Cro-Magnon, Homo sapiens sapiens is the direct ancestor of modern humans.

Homo sapiens sapiens is a subspecies of Homo sapiens, the only surviving species of the genus Homo and the hominid family. Therefore, their closest living relatives are the great apes (to which they belong), such as gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans.

Homo sapiens sapiens means “thinking man”.

Homo sapiens sapiens originated in Africa approximately 45,000 to 100,000 years ago and has since spread worldwide, including Antarctica. Its expansion in Europe coincides with the extinction of its contemporary, the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). In recent times, humans have even ventured beyond Earth and visited the Moon.

Discoveries at the Atapuerca site in Spain could significantly alter the chronology of prehistory in Europe. These fossils present a combination of traits that have led to the attribution of a new human species, Homo antecessor, a common ancestor of Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons.

In some classifications, the name Homo sapiens sapiens is replaced by Homo sapiens alone, considering it a monotypic species. This occurs in classifications where other subspecies are given the rank of species. Currently, scientists are still debating the proper taxonomic level, so both names can be found in texts to identify the phylogenetic line.

The evolutionary development that led to the appearance of early hominids began around 5.5 million years ago.

Hominids were the only primates who routinely walked upright. It seems their hands, feet, and bodies differed very little from ours.

They developed certain special features, summarized below, which took about 5 or 6 million years to evolve into modern humans:

- Good vision

- Upright posture

- Hands capable of a firm grip

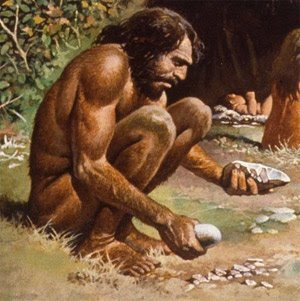

- Ability to make simple tools

- A relatively large brain

- Development of tongue muscles, which subsequently facilitated the emergence of language

Bipedalism

Hominids, bipedal primates, are thought to have emerged around 6 or 7 million years ago in Africa when the continent experienced progressive desiccation, reducing forest and jungle areas. As an adaptation to the savanna biome, primates appeared that could easily switch between bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion. Moreover, in an environment with warm temperatures and strong ultraviolet and infrared radiation, bipedal walking and the progressive reduction of body hair were advantageous adaptations, preventing excessive body heating. Around 150,000 years ago, North Africa experienced severe desertification, which exerted further evolutionary pressure, solidifying the main features of the Homo sapiens species.

To achieve upright posture and gait, major changes occurred:

- Skull: To allow upright posture, the foramen magnum (the hole through which the spinal cord passes from the skull to the spine) moved. While in apes, the foramen magnum is located at the back of the skull, in Homo sapiens (and their direct ancestors), it shifted almost to the base.

- Spine: The spine, relatively straight in apes, acquired curves in Homo sapiens and their bipedal ancestors, allowing better support for the weight of the upper body. These curves have a “spring” effect. Moreover, the spine could stand almost 90 degrees to the pelvis. Compared to a chimpanzee, the absence of a lumbar curve is noticeable; their body is pushed forward by its own weight. In the human spine, the center of gravity has shifted, so the body’s center of gravity is placed over the feet. Homo sapiens have a relatively large head, making their center of gravity quite unstable (and causing humans to tend to sink “headfirst” when attempting to swim). Another detail is that human vertebrae are more circular than those of apes, allowing them to better support vertical weight.

- Pelvis: The widening of the pelvis has been instrumental in the evolution of our species. The ilia of the pelvic region in Homo sapiens (and immediate predecessors) “turn” inward, allowing better support for the weight of the organs when upright. This modification to the pelvis involves a significant reduction in the speed humans can achieve when running. The upright position of the pelvis means that offspring are born “premature”. Human childbirth is called ventral angled because there is almost a right angle between the abdominal cavity and the vagina. In women, the pubic bone is almost frontal, while in all other mammals, the birth canal is very short. In Homo sapiens females, it is very long and winding, making childbirth difficult. As discussed below, this has been instrumental in the evolution of our species.

- Legs: Other very important and evident morphological changes occurred for bipedalism, particularly in the limbs and joints. The lower limbs are strengthened. The human femur bends inward, enabling humans to walk without rotating the entire body. The knee joint has become nearly omnidirectional (i.e., it can move in different directions). Although monkeys—for example, chimpanzees—have greater flexibility in the knee joint, this is for better locomotion in the treetops. Unlike their closest relatives, humans do not walk with bent knees.

- Feet: In humans, the feet have lengthened, particularly in the heel. Some toes have reduced in size, and the “big toe” (hallux) is no longer opposable to the other toes. The foot has almost completely lost its grasping ability. The human foot is no longer able to grip branches (as if it were a hand) and instead plays an important role in supporting the entire body. The big toe plays a vital role in achieving balance during gait and upright posture. The big toe of a chimpanzee is opposable, allowing the monkey to cling more easily to branches. In contrast, the aligned big toe of the human foot provides balance and forward momentum when walking or running. The leg bones are relatively straight compared to those of other primates.

Advantages of Bipedalism

The large number of anatomical changes that led from quadrupedalism to bipedalism clearly required strong selective pressure. There has been much discussion about the supposed ineffectiveness of bipedal walking compared to quadrupedal locomotion. Some have criticized the fact that no other animal that adapted to the savanna at the end of the Miocene developed bipedal locomotion. However, it’s important to remember that the type of quadrupedal locomotion used by some hominids is not particularly efficient. The way chimpanzees move, supporting themselves on the second phalanx of their hands, is not comparable to the gait of any other quadrupedal mammal. It may be sufficient for short distances on the ground but is not very efficient for long journeys in open terrain. Early savanna hominids probably had to travel considerable distances in open fields to reach groups of trees located far apart. Bipedal gait could be very effective in these conditions because:

- It allows scanning the horizon above the vegetation in search of trees or predators.

- It allows carrying things (like food, sticks, stones, or offspring) with hands freed from locomotion.

- It is slower than quadrupedal walking but requires less energy, which would be advantageous for traveling long distances in the savanna or in a habitat with fewer forest resources.

- It exposes less surface area to the sun and allows taking advantage of the breeze, which helps prevent the body from overheating and saves water—a useful adaptation in a habitat with scarce water resources.

Years ago, it was argued that the freeing of the hands by bipedalism in early hominids allowed them to develop stone weapons for hunting, which would have been the main driver of our evolution. It is now clear that the freeing of the hands (which occurred more than 4 million years ago) is not linked to the manufacture of tools, which happened about 2 million years later. It is also unlikely that early hominids were hunters; they probably ate carrion sporadically at best.

However, bipedalism surely brought a key advantage for survival: reproduction. The shift from quadrupedalism to bipedalism involved an anatomical change in the hips. This change widened the birth canal (by approximately 1 cm), making childbirth easier. Because this feature (bipedalism) was clearly advantageous, it became the defining characteristic of our species over thousands of generations.

Human Family Tree

Homo (Genus)

Genus Homo | |

|---|---|

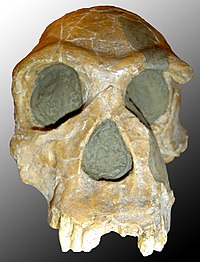

Skull of Homo habilis | |

| Scientific Classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primate |

| Suborder: | Haplorrhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | Hominina |

| Genus: | Homo Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species | |

| See text | |

Homo is a genus of hominid primates belonging to the tribe Hominini. The genus Homo includes modern humans and their closest relatives. The antiquity of this genus is estimated at 2.4 million years ago (Homo habilis/Homo rudolfensis). All species except Homo sapiens are extinct. The last surviving relative, Homo neanderthalensis, died out less than 30,000 years ago, although recent evidence suggests that Homo floresiensis may have survived until more recently, perhaps as recently as 12,000 years ago.

The genus Homo is characterized by bipedalism, with non-prehensile feet and the first toe aligned with the others. It exhibits encephalization and a fully vertical cranium. Among the characteristics that led to the separation of Homo habilis from the genus Australopithecus are the size of the skull and, more importantly, the ability to create tools.

Biological Evolution of the Genus Homo

The emergence of the genus Homo is subject to various interpretations. Sometimes, the theories offered by experts place the various Homo species in the same time period, making it difficult to specify the evolutionary line. Moreover, these interpretations are provisional and depend on research findings from fossils found so far. Therefore, new discoveries will inevitably lead to changes in theories about human evolution developed thus far. Even so, we present below a generally accepted view within the academic community.

Chronologically, Homo habilis is considered the first of our Homo ancestors. It appeared about 2.4 million years ago, and its name, “handy man,” comes from the belief that it was the first to develop stone tools. It is believed to have lived alongside different types of Australopithecus and that it was precisely the pressure from the genus Homo that led to the extinction of the australopithecines. Despite its apparent technological superiority over its predecessors, Homo habilis exhibited relatively few anatomical differences, although it possessed a slightly larger brain than earlier hominids.

Under traditional assumptions, H. habilis evolved into Homo erectus about 1.5 million years ago, a species that came to inhabit much of the Old World, from Africa to China and Indonesia. It began to be replaced by archaic forms of Homo sapiens between 400,000 and 250,000 years ago in different geographic areas. This archaic Homo sapiens had a larger brain but still had physical similarities with Homo erectus.

Following the findings in the Sima de los Huesos at Atapuerca in 1994 and genetic studies, a perspective of two evolutionary lines has emerged. The first, which developed in Asia and Europe, led to Homo heidelbergensis and from this to Homo neanderthalensis. The second, which developed primarily in Africa, became Homo rhodesiensis and subsequently Homo sapiens. This theory leaves open the debate about the origin of Homo erectus and its relationship to the species Homo ergaster and Homo georgicus. However, it seems clear that Homo floresiensis is the result of a specialized adaptation of H. erectus in a limited habitat.

The hypothesis of separate evolutionary lines is consistent with genetic studies supporting the theory of a single origin of Homo sapiens in Africa. This contrasts with the multiregional origin hypothesis, which assumes the simultaneous emergence of H. sapiens in Asia and Africa.

Hominid Evolution: Type Species

Homo Habilis

The first representative of our own genus, Homo habilis, is so named because its fossils were found alongside tools and stone chips, which have been termed the Oldowan industry.

Homo habilis was found in the same strata as fossils of Australopithecus robustus, indicating the coexistence of both species, possibly through a mechanism of ecological or ethological isolation.

Homo habilis lived approximately between 2.5 and 1.6 million years ago, at which point it became extinct. With a height of 150 cm and a weight of 50 kg, it was habitually bipedal. Its rounded skull had a capacity of between 600 and 800 cc, clearly larger than that of Australopithecus. Despite its marked prognathism and accentuated supraorbital ridge, its teeth were similar to those of humans.

Homo Ergaster

The first conclusive evidence of a species clearly resembling us comes from Kenya, where a fossil of an adolescent dating back 1.6 million years was found. This fossil presents a truly modern body structure with the same locomotion as modern humans. It is also characterized by a much larger skull and brain (800 to 900 cc), slender limbs, and an estimated adult height of 185 cm. This new body shape allowed survival in the open savanna, adapted to warm and dry conditions.

Homo Erectus

It is now accepted that, evolutionarily, Homo ergaster gave rise to Homo erectus, a hominid that arose at least 1.8 million years ago and disappeared about 200,000 years ago.

Homo erectus reached a height of 170 cm and had a large brain (800–900 cc, and even up to 1100 cc in the most modern specimens). Its teeth were clearly human-like, with incisors flatter than those of Homo habilis. Compared with modern humans, its skull was elongated. Its face was flat and sloping, and it had a very pronounced supraorbital ridge above the eyes.

Homo Antecessor

Once the genus Homo left Africa, human evolution played out on three continents: Africa, Europe, and Asia.

In the Sierra de Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain), fossils of a new human species have been found: Homo antecessor, dating back 800,000 years. This proves that Europe was already occupied by hominids at that time. They were, therefore, the first Europeans.

The cranial capacity of these hominids already exceeded 1000 cc, and they exhibited archaic facial features alongside a facial architecture as modern as ours.

Homo Neanderthalensis

It is believed that Homo neanderthalensis evolved from H. antecessor when it migrated to the Iberian Peninsula, via Asia, from Africa.

It lived in the Old World during the late Middle Pleistocene and early Upper Pleistocene (from 200,000 to 35,000 years ago) and became extinct around 35,000 years ago. The cause of its disappearance is unknown.

Representatives of this species had a strong build and an average height of 165 cm. The musculature of their hands, arms, chest, back, and legs was more developed than that of any current athlete.

Their heads, despite their primitive appearance, had skulls that, although longer than those of modern humans, were more voluminous and had a capacity of 1400 cc. They possessed dentition similar to ours, with large jaws and a weak chin. Their foreheads were sloping, their occiputs were bulky, and they had a prominent double supraorbital ridge.

It is important to note that Neanderthals were the first to ritually bury their dead, care for their elderly and sick, and exhibit aesthetic manifestations.

Evolutionary Progress

The most representative evolutionary advances present in most individuals of the genus Homo are:

- The progressive increase in brain volume, which has more than tripled during human evolution, a change attributed to changes in hominin behavior.

- A gradual increase in height and weight, reaching heights of 185 cm.

- A reduction in the size of the face, teeth (especially canines), and jaw.

- An increase in the number and complexity of stone tools and other implements.

Homo Sapiens Sapiens: Origin

Homo sapiens sapiens appeared in Europe during the last glaciation, around 40,000–35,000 years ago. This species has a globular head with a capacity of 1230 cc and a flat face with a sharp chin. Its forehead is straight, and it lacks prominent supraorbital ridges.

Hypotheses on the Origin of Homo Sapiens

Around 1.5 million years ago, perhaps more, hominids left Africa and spread throughout the rest of the Old World. But where did modern humans originate? Three hypotheses are proposed:

Multiregional Model

This model considers that the transition to anatomically modern Homo sapiens occurred simultaneously in different parts of the globe where archaic populations, descended from Homo erectus, lived.

According to this theory, archaic Homo sapiens populations interbred with modern humans, and the transition was driven more by local continuity in each region than by the formation of a new species.

Single-Origin Model

This model argues that Homo sapiens arose in Africa from archaic African populations that evolved on that continent for hundreds of thousands of years. It was only recently that these modern humans migrated to other continents and replaced the archaic populations established in Asia and Europe.

Interlinked Model of Evolution

This model attempts to combine the two previous models. It accepts, on the one hand, the existence of genetic exchange and interbreeding between populations and, on the other hand, regional developmental continuity across three continents simultaneously.